COMMITTEE OF THE PEOPLES CHARTER (ZIMBABWE)

SUBMISSIONS TO THE INCLUSIVE GOVERNMENT ON THE PENDING 2012 ANNUAL BUDGET

PRESENTATION BY THE MINISTRY OF FINANCE

THEME: A New Social Democratic and Social Welfarist Deal for Zimbabwe.

SUBMITTED

TO: The Ministry of Finance, Government of the Republic of Zimbabwe

THURSDAY 13 OCTOBER 2011

Cc: The

Prime Minister’s Office, The Speaker of Parliament’s Office, The Public Accounts Portfolio

Committee, Civil Society.

Contact

Details: 348 Herbert Chitepo Harare, Zimbabwe,

A. Introduction.

(i)

This is our considered input for consideration by the Ministry of

Finance as it prepares the projected national budget for the year 2012. It is important at the onset to make it

apparent that in presenting this alternative peoples budget framework it be

made apparent that the Committee of the Peoples Charter (CPC) submissions are

not made out of particular economic or financial expertise but commitment to

our country and commitment to democratic people centered government. And

in so doing, we wish to make it clearly

understood that these submissions are premised on our intention to see the

government prioritize the establishment of a Social Democratic ideological underpinning to the state, and a Social Welfare oriented national

economy.

(ii) We are also persuaded that any Zimbabwean

annual national budget should fundamentally serve the citizens of this country.

This makes such a policy document one that must have the approval of the people

of Zimbabwe, must talk to their collective national and individual aspirations,

address matters related to the livelihoods of contemporary and future

generations of the country and above all, seek to promote democratic, people

centered and accountable government within a Social Democratic and Social

Welfare framework.

(iii)

Furthermore, in the three years that have lapsed since the formation of

the inclusive government, it is publicly acknowledged and recognized that the

inclusive government, through the Ministry of Finance has, to its credit,

sought to ensure that there is public consultation over and around the

formulation of key performance priorities of the national budget. It is such an

approach to the national budget that has prompted the Committee of the Peoples

Charter (CPC) to make its input to the Ministry of Finance on this important

national issue. The CPC, in the interest of public transparency has also copied

these submissions to all the relevant portfolio committees of the Parliament of

Zimbabwe and civil society organizations with the intention of appraising

fellow Zimbabweans on our views on matters related to the 2012 national budget.

B. Founding Premise of

our Submissions.

(i)

The CPC is formed from the

processes that led to the establishment of the Zimbabwe People’s Charter that

was penned by civil society organizations in February 2008 at the Peoples

Convention held in Harare, Zimbabwe. Over 3500 representatives of civil society

organizations attended this meeting with the express intention of bringing to

the attention of national political leaders, in particular those that had been

involved in the SADC mediated negotiations in the run-up to the March 2008

elections, the priorities that any Zimbabwean government should consider

henceforth. The character of the output

of this convention was Social Democratic as well as keenly

focused on the deliverance of a state that is a Social Welfare state.

This is as outlined in the 7 key tenets of the Zimbabwe Peoples Charter which

cover the political environment, the national economy and social welfare, the

constitutional reform process, the youth, women and gender, elections and our

national value system.

(ii) With the passage of three years

since the formation of the inclusive government we are firmly aware that the

ideals enunciated in the Zimbabwe Peoples Charter have not been met for reasons

that include political contestations in the inclusive government; the

overwhelming of the initial signatory civil society organizations by the

politics of the inclusive government either by way of cooptation into

government programmes or through the

continued lack of enjoyment of their and fellow citizens fundamental human

rights to assemble or express themselves.

(iii) Regardless of these developments

over the last three years, the CPC has remained committed to the Peoples

Charter in so far as it provides a Zimbabwean Social Democratic and Social

Welfarist standard of measurement of the performance of the inclusive

government or any other Zimbabwean government of the past or of the future.

(iv) This standard, as outlined in the

Charter is premised on the history of our struggle for liberation and our post

independence struggles for full

democratization. Both eras of struggle

hold and still hold it dear that all human beings are created equal, have the

right to life and a life of dignity,

must be accorded the full enjoyment of political and economic freedoms

in any bill of rights as well as universal suffrage and social and economic

justice .

C. The Attendant

Principles and Ten National Guiding Points and Actions That Should Inform Our

National Budget.

(i) We realize that the inclusive

government is contested policy terrain given the different ideological

backgrounds of the three political parties that comprise it. This has meant that the national budget has

been characterized by politicized contestations as to how to reform and

revitalize the national economy. These contestations have also been

characterized by an unfortunate political party grandstanding at laying claim

to the incremental improvements that have been evident in the supply of goods

and services in the country.

(ii) In our view, it is therefore

imperative that the inclusive government considers re-thinking the national

budget in a different light. While it is accepted that the member parties of

the inclusive government are strange bedfellows and the workings of government

are generally informed by the politics of party positioning, the inclusive

government is failing to demonstrate the requisite ‘common ground’ that led to its formation. And it is this ‘common ground’ with particular regards

to the section of the preamble to the GPA that states, “committing ourselves to putting our people and our country first by

arresting the fall in living standards and reversing the decline of our economy”

that the CPC wishes to draw to the attention of the Ministry of Finance and the

entirety of the inclusive government.

It is also in the

following Section D of our

submissions that we emphasize that the inclusive government must of historical necessity take into account

the imperative that the national budget must be Social Democratic and Social

Welfarist in intent, purpose and practice.

D. Defining ‘Common

Ground’ In The National Economy.

(i) It is generally held as important

that national budgets should seek to address in a holistic manner, the

livelihoods and aspirations of all citizens in a given country. This includes

the responsibility of the government to provide health, shelter, education,

general welfare, employment, opportunity to be inventive and public transport for all, while at the same time providing for the

necessary expansion of the national economy to not only meet these needs but

also compete regionally and globally to be a developed and democratic people

centered state.

(ii) Because of our country’s history of

the liberation war and the continuing post independence struggle for full

democratization, both in relation to the full realization of envisioned

political freedoms and the realization of a people-centered national economy,

we hold it imperative that the inclusive government actively seek national

‘common ground’ on the national economy.

This is because where we have analysed

the politics of the liberation struggle and those of the struggle for full

democratization of the state as led by the labour unions in the 1990s, there are

threads that are common to both struggle epochs. The values of the liberation

war movements remain in tandem with those of the post independence struggles

for full democratization with particular emphasis on all players having

initially sought differing versions of a social democratic ideological thrust

to the state, upon independence or upon attainment of full democratization.

(iii) Evidence to the latter point resides

in the public knowledge that the main protagonists in the inclusive government

have generally referred to important national matters such as land reform or

indigenization as issues that they agree to in principle but differ in the area

of the methodology of implementation. It is our considered view that the

necessary compromise and in any event, the historically determined common

ground is that of having a national budget presented within the context of

social democratic ideals.

(iv) This would preferably be termed and

themed, A New Social Democratic and

Social Welfare Deal for Zimbabwe and would be characterized by the

following 10 (ten) national principles:

1. A re-affirmation of the liberation struggle and post independence

struggles for full democratization ideals based on the aspirations enunciated

in these same struggles which were and are primarily aimed at achieving

universal suffrage, democracy, political and economic freedoms, social welfare

and gender equality for all Zimbabweans.

2. A commitment to upholding the democratic truth that in the formulation of

a national budget, a sitting government of the day must ensure that there is

full declaration of the country’s assets, its actual revenue and its potential

revenue together with the sources of the same.

3. A continued commitment to seeking Zimbabwean solutions to Zimbabwean

problems within the context of a globalised World. This would take into account

the fact that it remains Zimbabwe’s national prerogative to negotiate with the

World in what is democratically held to be in the country and citizen’s best social

democratic interests.

4. A commitment to the re-establishment and improvement of a social welfare

state. That is, a state that understands and implements the provision of

health; education for all; public

transport; basic nutrition for children

according to UNICEF standards; access to water; employment creation; social welfare grants for

the unemployed; specific social welfare grants for women; and natural or human made disaster support

for all its citizens.

5. A commitment to the full enjoyment of universally accepted and

acknowledged human rights; the rule of

law and the separation of powers that are expected in a democratic state.

6. An understanding that it is obligatory upon the state to ensure equitable

just and accountable re-distribution of the land for the benefit of the

majority rural and urban poor in order to guarantee their food security. This

would entail that the state establish an independent Land Commission

7. A commitment to the democratic imperative that all national wealth

acquired from our natural minerals must be harnessed primarily to provide

resource support for the social welfare needs of the country’s citizens i.e

education, health, public transport, access to water and basic nutrition. In

tandem with this commitment that the government must commit itself to public

disclosure as to the amount of revenue it has acquired and will acquire from

all of our national mineral wealth for the full knowledge of the public.

8. A re-commitment and pledge to gender equality in all spheres of

Zimbabwean society and the active

promotion of women’s rights as well as the protection of the rights of young

females. This includes giving preferential treatment to young females in the

arenas of health, education (both basic and tertiary), and in employment. It

also includes ensuring a special social welfare grant be given to all women

headed households and disadvantaged women in general.

9. A re-commitment and pledge to ensure that all young people of Zimbabwe

have access to free and quality education up to tertiary level, access to

health, access to employment and access to social welfare grants where they are

economically disadvantaged.

10.

A re-commitment to solidarity with

the peoples in the Zimbabwean Diaspora, the peoples of Southern Africa and the

African continent premised on accepting the ideals and principles of democratic

governance grounded in a firm understanding of our shared struggle histories

and our continued struggles for the assertion of African identity, unity and

solidarity with the rest of the world. This understanding will also reaffirm

our commitment to the United Nations Charter as well as the United Nations

Declaration of Human Rights with its attendant Conventions.

E. The Pragmatic

Urgency of the 2012 Budget Minus Political Expediency.

(i) We are

aware of the urgency of the 2012 budget in relation to our ongoing national

economic crises wherein our social service provision has remained low, unemployment

levels remain high and our industries are yet to regain the momentum that was

lost in the last 15 years.

(ii) We are

also cognizant of the political decisions that will inform the allocation of

resources for a national Constitutional Referendum and a General Election.

(iii) It is

however our considered view that the national budget should not be beholden to

these two processes without addressing the nine principles enunciated above.

(iv) To ensure

that this does not happen we strongly recommend a clear demarcation in the

national budget to matters related to the functional components of the national

economy from the political ones that have been pre-determined by the GPA. This

is to say, where the government has budgeted for the political processes of

referendum and elections, the political implementation matrix unlike in the

last two financial years, should not evidently cause unnecessary stagnation in

the provision of the social welfare needs of the people of Zimbabwe.

(v) It is therefore

our considered proposal that the Ministry of Finance makes the following

distinction in the national budget:

1. The ‘Common Ground’ Functional Economic Provisions: these budgetary provisions would

take into account what we have highlighted as the ‘common ground’ that the

budget must address. These provisions essentially point to matters that should

not be directly beholden to any decision by the three principals in the

inclusive government post their agreement to these same said ‘common

ground’ principles. For emphasis, these

provisions should also include budgetary allocations for the enjoyment of our

human rights and political freedoms as well as the rule of law and be firmly

grounded in Social democratic and Social Welfarist ideals.

2. The Contingent GPA Provisions: These provisions will be set aside to ensure that political

contestations via democratic elections are provided for without undermining the

national economic ‘common ground’. This would mean where and when the three

principals to the GPA decide to call for elections, these political processes

should not stop the functioning of the state in relation to its ability to

provide essential services as occurred in the contestations between 2000 and

2008.

3. It’s Our Country too. Such provisions will make it clear to the people of Zimbabwe

that whereas the politics of our national leaders remains important in relation

to who is in charge of our government, in the event that they disagree as they

have done in the last two and a half years, our country should not be permitted

to collapse on that basis alone. It is the prerogative and duty of all citizens

to remain committed to the Zimbabwean state, hold it to account on broader and

non partisan values that assert our collective humanity and where possible,

avoid the proverbial circumstance of ‘when elephants fight, it is the grass

that suffers’.

F. The Proposed

Priorities for the 2012 Budget.

(i) For emphasis and with due

consideration of the economic circumstances that the country is facing we

humbly propose that the inclusive government prioritizes the following in its

2012 Budget:

(ii) ‘Common Ground

Provisions’

1. Restoration of full functionality and

professionalism at all major referral government and local government hospitals

in Zimbabwe inclusive of free treatment and medication for the majority poor;

free and guaranteed access to electricity for all of these hospitals, fair

remuneration for all medical personnel and the re-launch of a health for all

nationwide awareness campaign.

2. Provision for free primary school

education for all, subsidization of all government secondary school budgets,

restoration of the student loan schemes for tertiary education in collaboration

with university and college administrations and the establishment of a national

education policy that is much more sensitive to the aspirations of Zimbabwe’s

Generation Next.

3. Provision for Parliament that relate

more to its oversight role than it does to the remuneration of Members of

Parliament without being over-reliant on donor funding. This will serve to

guarantee its independence.

4. Provision for a fully functional

Judiciary, with permission for greater decentralization of its functions for

the full implementation of the rule of law and guarantees to its independence.

5. Provision for the land reform

programmes hitherto, with access to agricultural inputs and

infrastructural developments remaining a

priority; the land audit becoming a reality; the establishment and full

functioning of an independent land commission as well as compensation for those

who unjustly lost their livelihoods during the various phases of the land

reform programmes after independence.

6. Provision for the revival of a electricity,

road/ rail and telecommunications systems

in order to improve public transport and communications. This would entail an

revised incorporation of the National Railways of Zimbabwe and its national

rail network with particular emphasis on urban passenger services as well as

urban-rural passenger services; a revitalization of our fixed telephone

networks to intergrate them with our mobile telephony for greater communication

between citizens and the urgent refurbishment of outstanding power stations.

7. Provisions for the utilization of

revenue from the entirety of the mining industry into the national health

system to purchase modern and up to date medical equipment, drugs as well as input directly into the

revival of our national emergency response systems such as the Fire Brigade,

Civil Protection Unit, and ambulance services.

8. Provision for the expansion of the

ability of Zimbabweans to receive and impart information through the

establishment of a separate Media Development and Diversity Fund to assist in

the establishment of independent private and community radio stations, boost

transmission capacities of the same and assist the print media in their

viability challenges.

9.

Provision for a holistic review of all state enterprises within the

context of having their functions fulfill the New Social Democratic and Social

Welfarist Deal for Zimbabwe.

10.

Provisions

for a ‘Bridging the Gap’ Re-intergration and Linkage Fund for the Diaspora with the express aim of

ensuring that we communicate and integrate the Diaspora into our national

debate and our national planning processes.

11.

Provisions

for the revival of our industrial sectors in relation to basic commodity

production, mining, agriculture, tourism, industrial and mechanized heavy duty

production, information communications technologies, all premised on the

understanding that their operations are predicated on a Social Democratic and Social

Welfarist societal vision and reality.

12.

Provisions

for the on-going global efforts to tackle the global problem of Climate Change

which will include a much more comprehensive funding programme for the

Metrological Department, the re-invigoration of our public awareness campaigns

on clean and eco-friendly environmental usage, that also is cognizant of the

dangers of seeking Foreign Direct investment in bio-fuels that damage the

environment.

(iii) ‘GPA Provisions’

1. Provisions for the finalization of

the constitutional reform process with

acknowledgement that it remains the right of Zimbabweans to reject or accept

the draft constitution being written by

COPAC. Further still, to provide necessary resources for knowledge

dissemination on the end result of the COPAC constitution as well as potential

re-engagement with the Zimbabwean public on the aftermath of the COPAC process

regardless of its outcome.

2. Provision for the continued reform

and full functioning of the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission and the attendant

enabling legislation with the express

aim of fully democratizing electoral processes in Zimbabwe.

3. Provision for a national elections

referendum, i.e to hold a national referendum on whether or not the country is

ready for elections given the pace and progress of reform.

4. Provision for national elections in

the aftermath of a national referendum to determine the nation’s satisfaction

with the relevant electoral reforms.

5. Provisions for transitional justice

processes in the aftermath of a national election.

G. Conclusion

The significance of the national budget cannot be more

apparent in our country, wherein, it represents a binding statement of intent

by the inclusive government to continue to seek solutions to our national political,

economic and social crises. Our submissions may, in some instances be deemed

idealistic or lacking in pragmatism. Where we are accused of being idealistic

we humbly submit that it is from our ideas that we become pragmatic just as it

is from believing in God, that we learn to bend on our knees in prayer. Our

submissions do not cover all aspects of the national budget, neither do they

undertake technical analyses of the National Fiscus. They do however take into

account, the realities that are faced by millions of Zimbabweans (at home and

abroad) and by so doing, offer a perspective that is intended to inform the

policy intentions of the inclusive government for the year 2012. As explained

in the first sections of this document, the basis of our submission is the

Zimbabwe Peoples Charter. This is not to say that the latter is a perfect

document, but it demonstrates a necessary understanding of the importance of

accountable and democratic government particularly so, in the context of our

country’s historical, contemporary and future challenges.

ENDS///

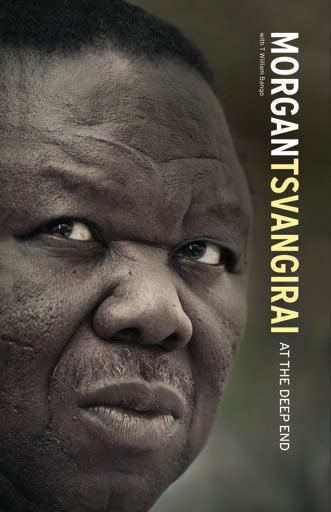

The surprise components

of the book are to be found in the revelations that the Prime Minister makes in

reference to his party’s history and his interactions with other leaders. He

also surprisingly refers to the ‘no vote’ in the constitutional referendum as a

mistake ‘with the benefit of hindsight’

a point that is controversial on its own. Some

of these revelations have already been published locally and on the internet in

the print and electronic media.

The surprise components

of the book are to be found in the revelations that the Prime Minister makes in

reference to his party’s history and his interactions with other leaders. He

also surprisingly refers to the ‘no vote’ in the constitutional referendum as a

mistake ‘with the benefit of hindsight’

a point that is controversial on its own. Some

of these revelations have already been published locally and on the internet in

the print and electronic media.